"Western Africa 2012" story # 5

THE N-420 (TARRAGONA TO CUENCA)

Cuenca, Spain

May 12, 2012

Traveling, you sometimes needed less time than expected to get to your destination. But, you usually needed more time. Sometimes, you needed a looot more time.

On my way to Morocco, I stayed at my friend Xexi's place long enough to join him and his family for Sunday lunch. We went to his parents' home, where Mother Paquita was the cook. I was surprised, and delighted, to see about eighteen different dishes on the table. Wow!

We ate:

eggplant mixed with ham and cheese, to form patties which were fried in egg and bread crumbs

"batatas bravas" - bits of baked potato with aleoli (a garlic cream made with egg, oil, and salt) and black pepper

sweet dates with bacon wrapped around them, baked in the oven

flimsy clear cuttlefish pieces in a tomato sauce

big pink prawns, boiled or grilled (Only Paquita's finicky cat could tell the difference between the boiled and grilled ones.)

a liquidy, gray mixture of duck liver and cream, mixed with pasta and baked in the oven with cheese on top

for dessert, a chocolate-and-yogurt cake called "coca"

for the second dessert, a thin and crusty pastry made with apples

and much more. I was happy I wasn't rushing out of the Barcelona area!

That evening, Xexi and I ventured into "Cafe de la Havana" in his town of Mataro. I wanted to dance some salsa and some bachata. The girls here quickly impressed me. Dancing with me, they wrapped their arms around my upper body and rested their cheeks against mine, as I moved us ever-so-slightly to the music, just enough for it to still be called dancing. And the prettiest girls - including one whose black ponytail was pulled tightly back to show off her creamy baby face, and who wore a short, orange poofy dress - danced the closest.

Barcelona had made a good impression on me.

Friendly, pot-smoking Xexi told me, "You have a home here." He (a.k.a. Sergi) had lived with my family in Michigan in the past. He said my younger brother, if he ever wanted to visit, had a home near Barcelona, too. A female friend of Xexi's misunderstood this. "Justin's brother has a 'casa' (house) here?" Xexi explained, with a dark-bearded smile, "Well, actually, I am the only one who has a home here ..."

In a country where so much pot was smoked, it was ironic that the road which I'd take to travel south was called the N-420. It was a small highway, going through small towns. I'd tried to hitchhike on an expressway, but I gave up after spending ten hours trying in vain to find a ride which could take me past Barcelona. The N-420 would be a slow road to travel on. But, I would see more of Spain, catch quicker lifts, and hopefully have fun.

For my first three rides, I waited a total of fifteen minutes. Ah ha! No standing around and waiting for me! They only took me a total of ten kilometers, though.

My third driver took me to his home in the village of Riudecols. To do this, he drove up steep roads that zigzagged narrowly between four-story buildings. The village grew out of a massive hill. My driver's home was one of these four-story buildings, and it had been in his family since it had been built in the 16th century.

With the shutters closed, it was gorgeous inside. The damp entryway was two stories tall, so I could see the dark second floor and the wooden beams supporting it and the even darker first floor. The second floor was low-ceilinged and white, with bits of artwork everywhere: antique heavy mahogany chairs, porcelain figurines on the lamps, stormy paintings. This driver, Lorenzo, had dedicated his life to studying culture. We discussed Tolstoy. He (Lorenzo, not Tolstoy - but possibly Tolstoy, too) was gray-haired and big-bellied and independently wealthy. He owned another six houses, at least.

Like many rich people, he:

1. disliked most of his fellow townspeople.

2. gave little, and expected a lot in return.

3. was confident.

4. spent a lot of his time worrying about his possessions.

He'd lived in Barcelona, Paris, and Geneva, and he'd met descendents of James Joyce, Paul Valery, and Tolstoy. I joined him (Lorenzo, not Tolstoy) for lunch. I ordered "crema catalana" for dessert. This yellow pudding had an ice-like sheet of burnt sugar on top. Mmm!

I traveled onward. The N-420 passed towns made of the stone (sometimes reddish, sometimes coffeeish) they were mounted on. Square Medieval towers and soaring church spires called to me to stop and get to know them.

A driver named Felipe would invite me into his home next. Another well-cultured man, he made his living by buying artwork in Cuba and selling it in his galleries in Spain. This tanned man spoke often about morbid things.

There were many mass-graves, he said, scattered in the hills between the towns of Gandesa and Calaceite. The dead had died fighting in the Spanish Civil War of the late 1930s.

American, Canadian, Cuban, and Mexican socialists had come to fight against the Fascist dictatorship of Franco. One night, in an offensive move, the foreign socialists crossed the Ebro River which flowed through Gandesa. Their objective was to reach some fortresses near Calaceite. But, they were met by an opposition that included Italian soldiers, German soldiers, and Moroccan mercenaries. They never accomplished their objective. And many of their bodies were never recovered.

Felipe drove me into coffee-colored Calaceite. The village had been settled by Hebrews. Were they still here? I asked. No. The Jews had been forced out during The Inquisition; they'd gone to places like Morocco. Calaceite's architecture was like something from five centuries before Christ, Felipe said. Hm, I would have to take his word on that. I hadn't been around then.

But, I was around now to go for a walk. The old town wrapped around a hill. Its three-story buildings connected to one another over my head on the streets, or they opened up for me as steps tunneling their way beneath buildings. Hebrew arches led me under 11th century buildings, to stone benches I could rest on. Occasionally, as I wandered through the alleys, I came to dead ends. Ivy climbed over the stone homes, so silently. These dead ends surprised me. They reminded me I wasn't in a fantasy world. They reminded me of when I wanted to do something in life but was unable to.

As I took pictures, I was attracted most to one scene. Between a black jointed street-lamp leaning outwards from a wall, and a ridiculously tiny balcony, was a street name: "Calle de la Soledad" (Street of Loneliness).

I ate lunch with Felipe that day. His old home had been remodeled with new wooden ceiling beams recently, and bright Cuban paintings hung from the wall. Yet, it was still damp.

We filled up on moist and wobbly goat-cheese, hard yellow goat-cheese, moist pinkish sausage, and black olives. A well-traveled man, Felipe said he loved Mexico and was fascinated by the cruel business of narco-trafficking. He said, the way he figured it, every line of cocaine signified a rape, and every gram of cocaine signified the murder of a child. I liked how he put that, as it placed responsibility on drug-buyers for atrocities committed in their drug's name.

I moved on from Calaceite.

A young family drove me to Alcaņiz. They also took me to their home. This home was squeezed into the old "Arabic quarter", where the narrow lanes were said to be straighter. The family's kind father - shiny-black-ponytailed Jorge - loved that these streets were always full of children.

Jorge gave me a tour of his town. He said the castle on top, with 14th century etchings of the Last Supper fading upon its stones, had belonged to Christian monk-warriors. They'd been too brutal to the townspeople, though, and so the town had overthrown and killed them and taken control of the castle.

In more recent times, the people of Alcaņiz had overthrown the "Nationalist" supporters of Franco during the time of his dictatorship. They established anarchism. Everyone worked the land - including the formerly rich Nationalistas - and everyone benefitted from his own work. Anarchism prevailed for a while, until Franco bombed the town or sent his forces in. Cruelty was then repaid for cruelty; and the Nationalists punished the anarchists.

After two days, I said good-bye to Alcaņiz and its 15,000 people - who were not so cruel today. I thanked Mother Nuria, who had a beautiful gap between her teeth, and Lucas and Leo, who had their parents' thick black hair hanging over their eyes, and Jorge.

From Alcaņiz, I traveled quickly. I passed the town of Montalban, where radioactive red rock formations tumbled upwards to plateaux covered in pine forest.

Near the town of Caņete, where the mountaintops were castle walls, the hitchhiking slowed down.

I was surprised and relieved when a semi-truck stopped for me. Spanish trucks almost never picked up hitchhikers. The controlling insurance companies forebade them to. And the unsympathetic police enforced this law.

"O boy, management with neckties on! -- Markell insurance men who stop trucks & throw hitchhikers out." - Jack Kerouac

This trucker, Arnau, was delighted to have me with him. I asked if he knew any other reasons why Spain was such a tough country to hitchhike in. He suggested it was because the Spaniards had lived for so long under Franco's dictatorship, from 1938 to 1975. The Church had been forced on them. They'd been isolated. Now, they distrusted strangers and foreigners.

Maybe. But, I had a theory of my own. The Mediterranean cultures - Spain, Italy, Greece, Israel - seemed to have primitive values: business, family, outward appearance and fashion, pleasures of consumption. Most people read little and traveled little.

And some of these countries' work-days were broken up by long, afternoon "siestas". Thus, they weren't truly free from work until late in the evenings. This gave them little time for art and leisure, or to philosophize on such things as social issues and altruism. And: Why pick up that weird hitchhiker?

Having said this, however, I'd add that the Mediterranean cultures were home to some of the world's most progressive-thinking people. Israelis had constructed revolutionary communities and schools, and they were kind to hitchhikers. A significant percentage of Greeks voted "communist". And Spaniards put up posters calling for "horizontalism" - a political system in which there was no elected hierarchy, and all people resolved issues as equals.

Progressive-thinking Jorge and Nuria had impressed me in Alcaņiz. They grew almost all of the food they ate in Jorge's garden. Jorge grew almost every vegetable imaginable; pea-pods were in season now. Also, he (a massage therapist) had bought his three-story home with cash and remodeled it himself. Thus, they were free from banks and supermarkets. Bravo!

Another thing which threatened the freedom of hitchhikers worldwide was "The News".

Xexi had told me, years ago, he thought the American media was trying to inject fear into its people. This year, a doctor in Alcaņiz told me the United States controlled the global media. It had been obvious, in the Czech Republic, that the news was only showing scary stories about criminals. There weren't only criminals in the world! I wished people would stop watching The News.

Traveling onward, I reached the town of Cuenca. I was now less than halfway to Morocco.

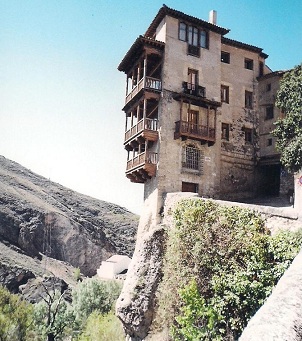

Cuenca's old town perched upon a dangerous, deep cliff in the mountains. Its most-photographed house boldly dangled three floors of balconies over the gorge. The balconies were made of a burly wood like cedar, with fancy banisters and saddle-shaped supports that reminded me of an Old West saloon, or a house haunted by ghosts. The house dated from the 14th century. The 1400s. Or the 1300s? The 1300s. Wow!

Elsewhere, the old town dipped down more gently towards the new town. A row of six-story buildings, adobe-white or orangy-cream or light beige, stuck out from above. Thin and crammed together like books in a bookcase, each hung further or less far out than its neighbor. Some jutted out over nothing but a few wooden braces and supports. And there was no pattern to the size or location of their dark windows. Picasso paintings looked like this.

One of the charms of Cuenca was the way in which the houses were painted: a soft and blotchy way, which allowed you to see the hot and cold sides of the color, as on a fluffy pillow.

Sky blue. Creamy orange. Mustard yellow. Ivory. Elephant-toe gray. Dried blood. Coal. Periwinkle purple. These colors comforted me in the high town's Plaza Maior. A silver shield, brandishing flags, blocked one end of the plaza but allowed cars to drive through its three arched openings. Pedestrians sat at sidewalk cafes, eating tapas and talking loudly. And above everything, the statue of an aggressive bishop attacked from the starlight-white facade of a huge cathedral. Two arches behind him led only to the night sky, and heaven.

I walked from the old town across a pedestrian bridge that spanned the gorge. It led to a mountain with nothing on it but one hotel, and cliffs for rock-climbers to enjoy.

I slept peacefully, in my tent.

Modern Oddyseus.

Thanks to Viviana; Gabrielle; Carlos; Diego; Kiko; Felipe Sanmartin Suņer; Jorge, Nuria, Lucas, & Leo; Juan; Danu; Jose; Jorge; Javier; Valerio, Ophelia, & Adrian; Miguel; Matilde; Arnau; and Simon & Michael for rides!

Much thanks to Xexi; and Nuria, Jorge, Lucas, & Leo for places to stay!