"Western Africa" story # 22

MORE SUFFERING

Bubaque, Guinea-Bissau

September 21, 2012

Just as all signs of my foot infection were disappearing, I got diarrhea.

Just as soon as I had become cured of the diarrhea and was beginning to feel completely healthy, I got diarrhea again.

Just as my stomach was beginning to feel better, I started to feel like I had a fever. I went to the hospital, where a nurse sold me quinine and amoxicilina to cure me of malaria (a second time).

Worst of all, my tooth started hurting me. A penniless musician from Conakry - who had blackish brown teeth to begin with - complained to me that the rainy season decayed teeth quickly.

Actually, I had only sensed that the tooth might some day begin to start hurting me, a little itsy bit. (Don't worry, Mom!) That was enough to convince me to immediately give up eating chocolate spread.

(Smart move, huh, Mom!?)

Earlier in the year, I'd gotten some cheap dental work done in the Czech Republic. The dentist had given me a shot of antisthesia that failed to numb my mouth. I could feel her drilling the whole center out of my tooth and striking the gum. Then, instead of filling the cavity, she seemed to miss her aim and fill the space between this tooth and the next. But ... at least I'd saved a few bucks on the dental work!

Five months later, in Guinea-Bissau, this problem forced me to give up chocolate spread: the backbone of my diet, the muscle, the ... brain of my diet. A Catholic nun here informed me that sugar stimulated the brain and thought. That was probably why I was able to learn so many languages.

"Justino, mana?" (Justin, how are you?)

"Na ekoyoke. Mana?" (My stomach hurts. How are you?)

"Nyakanango. Monyake?" (I'm great. Have you woken up?)

"Ee." (Yes.)

"Midanei?" (Where are you going?)

"Nyidan kopakpo." (I'm going to the port.)

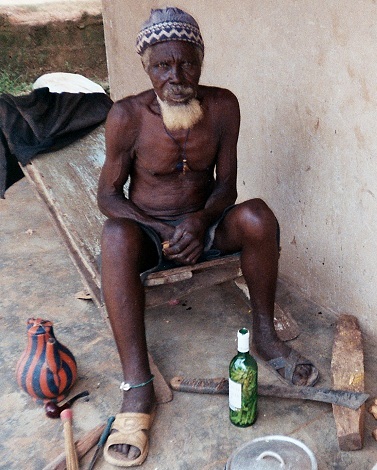

This conversation, between me and white-bearded Tio Morado Lopes who sat outside mixing traditional medicines all day, held in the language of the Bijagos, should serve to prove ... something ... about what I was talking about earlier. What? I forget now. My brain hasn't been working too well lately.

In addition to the chocolate spread, I lost my appetite for rice and fish. It was bound to happen some time. The diarrhea which I now associated with the dishes cooked by my generous neighbors probably had something to do with it. The chocolate spread used to serve as a sort of glue in my stomach, making me invincible to diarrhea. But, those days were over ...

The problem with my possibly-one-day-going-to-start-beginning-to-start-hurting-me-in-the-distant-distant-future tooth (don't worry, Momma, I wasn't going to come home with a mouth full of gums!) was that it left me hungry. I went to market to see what the local women were selling.

Fruit?

A small, red fruit which grew in bundles on palm trees could be mashed and eaten, though this sweet pumpkin mush was full of inedible seeds and slivers. There were also tiny lemons.

Vegetables?

Onions, garlic, small tomatoes, big cucumbers, dirty carrots, tiny eggplants.

Chicken meat?

No, but chickens walking around town were for sale for $3 apiece.

Beef?

On Friday mornings, it was possible to buy beef.

Fish?

Small fish, ugly fish, long fish, flat round fish, one fish, two fish, red fish, blue fish.

I didn't know how to cook and/or feather half these things. I called to Claudia and Sara, the penniless Portuguese girls who'd left the island ten days ago, and offered them jobs as my cooks. They'd consider the offer.

Around this time, my boss Father Luigi gave me, from his private garden, three big avocados and three giant pandas. Oops! I meant to write: papayas. I was so happy to receive these giant papayas. My wise and loving Mom (it had always been her wish that I should have all my teeth) said of the fruit: "Some things are worth more than gold."

Yes. And I was finding out, it was fairly difficult to live in this place.

One evening, near my home, a young woman moaned a song for all to hear. I learned her two-year-old son had just died. She continued her song until late that night, though it died down in volume, and she began bawling again in the morning.

Three nights later, I was awoken by a commotion. I could hear a woman slapping someone, being slapped, shrieking. I heard the cries of a child. I ventured outside. A small boy was being treated by one of the old men who lived beside me; the boy's mother was writhing around in panic; and other people shone dim flashlights on the scene.

A shiver ran through my spine. I recalled Father Luigi's thesis in anthropology, which I was currently editing for the internet. It said that, in Bijago culture, the dead were summoned shortly after their deaths in order to determine the reasons for their deaths. Was I seeing a dead boy!?

No, probably not. The dead didn't return in person. Their spirits returned in straw coffins made for this ceremony, empty coffins which became heavy like corpses and moved around in the hands of those who carried them.

No. The child I was seeing had a swollen left hand and belly. The traditional doctor washed the boy's hand with an earthy liquid, caught this same liquid in a bowl, and had the boy drink it. The doctor wound a palm leaf tightly, and stuck it way down the boy's throat. The boy, in the firm grip of one of my neighbors, screamed and leaked tears. His frantic mother crawled on the ground and tried to pull the leaf out of his mouth.

Man, there was a lot of suffering involved with having kids, I thought.

The old man advised the mother and child to go to the hospital. I would later hear that the boy had been bitten by a snake while playing, and that he didn't die.

This port town of Bubaque, in the Archipelago of the Bijagos - despite the fact that people never said bad words about others, that they invited strangers to eat, that they always answered, "Nyakanango," or at least, "Um pouco bem" (A little well), when asked how they were doing - had given me the impression of being a sad place of suffering.

Why?

Almost all of the businesses were owned by non-Bijago people: Muslims, mostly.

Every day, Bijago people begged from me. They wanted money to buy bread, medicine, wine. When I wasn't feeling great, this was an added pressure on me.

I saw few signs of the rich culture Father Luigi had found here in the mid-70s. It seemed to me, the people mostly sat around. I often sensed a sweet, tainted taste on their breaths, evidence they'd been drinking wine made from the yellow "caju" plum.

Father Luigi's thesis had told about a very communal culture, a structure in which men sacrificed themselves for their villages until they were thirty-five, a people who gave presents to and obeyed the elders. The society sounded well-organized and strong.

Bubaque seemed to be the site of the crash between such a culture and a world that used money, that listened to selfish rappers on the radio, that invented power-hungry and judgmental Gods. The calm waters of the archipelago had met the rough Atlantic.

Maybe my impression of the place would be different if I went to the remote villages, if I saw her during the more active "dry season", if I had some beef (and chocolate spread) in my stomach?

keep your head up

on the road,

Modern Oddyseus