"Western Africa" story # 32

THE PASSING OF AN AFRICAN REVOLUTIONARY

Bubaque, Guinea-Bissau

November 12, 2012

While still in Guinea-Bissau, I'd received an email from Ziguinchor, Senegal. It bore bad news:

Nfally Souane was dead.

This cuddly 78-year-old, who'd undermined French rule during colonial times and expressed solidarity for great African leaders, had passed away. On September 29th, 2012, two months after he'd hosted me. Even when I visited him, his health wasn't that good. He got malaria and stumbled around, dizzily.

I sent my condolences to the family. "Sindi indigallah," was what one said at times like these in Senegal.

I was sad. Because I didn't know who else to tell of Nfally's death, I told the only African revolutionary I knew in Guinea-Bissau: Babacar Saar.

Sixty-seven-year-old Babacar Saar lived on the other side of the road from Father Luigi's house. In fact, the two men had cooperated in making Luigi's first NGO, which provided fishermen with motors in exchange for money to be paid later, until the price of gasoline rose too high to make this project feasible.

Today, Babacar was the head of a housing complex that included a few large buildings and which sometimes had electricity at night. He had four wives who sold vegetables in the local market and dried fish in Bissau. He'd had more than fifteen children, one of whom maintained an Islamic study center in his yard. Also in this yard, fishermen constructed giant canoes. A small beach lied behind Babacar's house.

He had the same light-tannish skin as his daughter, Tida. He rested in his chair and wore silk, maroon Islamic robes. He couldn't speak Bijago, because he was a Fula. He couldn't speak Portuguese, probably because he didn't want to. He and I spoke French together. The old man spoke softly, happily.

He told me he'd fought the Portuguese during Guinea-Bissau's eleven-year war for independence, that ended in 1973.

In 1968, his right knee was filled with shrapnel, but he continued fighting. The ugly shrapnel remained in his knee to this day; it hurt him whenever the tide was coming in. Doctors called him, "a miracle".

Sometimes, pieces of shrapnel worked their way out of his knee, as one did this October. I congratulated him once he told me about this.

He said the Guineans had had no military technology. Fighting the Portuguese, they stayed in the forest. Meanwhile, the Portuguese recruited seventeen-year-old Guineans, by threatening to kill their parents if they didn't fight for the Portuguese side.

The Guineans had been aided with arms from Russia. Perhaps in exchange for this, Babacar traveled to Russia at some point to serve Russian interests in Chechnya.

The Guineans were aided with troops from Cuba. Babacar commented that Fidel Castro was "brutal". I asked what the Cuban troops had said of Castro and Che Guevara. He said, "Some said good things, some said bad things."

The Guineans, themselves, had a great leader during their war for independence. His name: Amilcar Cabral.

Nobody ever talked about Cabral these days, at least no one ever talked about him to me. I only read a bit about him in Luigi's thesis.

He'd had a great vision for the independent Guinea-Bissau. Freedom and equality were the rights of all people regardless of ethnicity or color, he believed. People mustn't give up their ethnic heritage nor traditional beliefs in order to be welcomed as valid members of the nation, as they were forced to do under the Portuguese.

In one speech during the war for independence, he said: "We intend to build a nation in which everyone, regardless of where he came from, can live, work, and think freely. The only requirement is that he respect the leadership of others."

In addition to the leadership of Cabral, this country-to-be was gaining unity through the adoption of a national language, Creole. Though derived from Portuguese, it included traditional Guinean grammar. It enabled people of different ethnicities to be friends, and to do so speaking a non-colonial language. Indeed, the colonialists had considered it a "badly-spoken Portuguese" and banned it.

In spite of the wrongs committed by the colonialists, Amilcar Cabral never antagonized the Portuguese people. He believed it was not only the oppressed who needed liberation but also the oppressors. He realized that the people of Portugal were currently being oppressed as well, by their dictator Antonio de Oliveira Salazar. When Guinea-Bissau would achieve its independence, the Portuguese troops were allowed to leave peacefully.

Unfortunately, Amilcar Cabral died on January 20th, 1973, eight months before independence.

I wanted to ask Babacar what he knew and thought about the legend of Cabral.

But, Babacar was hospitalized during my last two weeks in his country, with high blood pressure.

I went to visit him in the hospital. I wanted to greet my friend.

But, all he did was sleep.

I wished he'd return home soon.

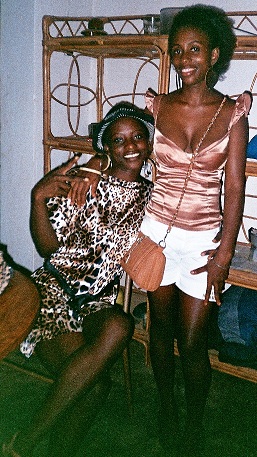

In the meantime, I figured the least I could do for him would be to keep his gorgeous, voluptuous daughter company.

On my second-to-last night in the archipelago, the moon was full and the tide was high. So, Babacar's proud daughter and I went swimming. Short-haired Tida Saar wore a maple bikini, and sat in the surf. She whispered, "Te amo muito." (I love you a lot.) This evening would surpass my slam dunk in the Rymarov Basketball League as being the best moment of my trip. It was my thirty-third birthday.

Walking home, I was happy. I knew I loved her, too. I loved her because:

She drew pictures in the sand. She played soccer aggressively. She had a sweet, squeaky voice that became more loving the more I knew her. She wore torn, silk nightgowns during the daytime. She suffered for those whom she loved: her closest sister had died as a teenager; a boyfriend died in a motorcycle accident; she maintained a relationship for two years with a British boyfriend who would never visit her. "Quem sofre, vence," she said. (Who suffers wins.)

We enjoyed our last night together. And then, on October 28th, we said good-bye. I would go to spend six weeks in Morocco.

I hoped she wouldn't suffer for me. I felt consoled to know she was remaining with the person whom she loved most. Her ten-month-old baby, Baby Erwin.

I was going to miss those two.

Thanks, Bijagos and non-Bijagos, for a great stay in your land!

Modern O.