"Rest of the World 2013-14" story # 13

GENOCIDE

Yerevan, Armenia

October 15, 2013

The city of Yerevan - as seen from above - was a smoky gray, brown color.

On the days when I'd slept on a mountain in the city, Yerevan's circular center spread out below me. It shined with lights, cars, and people. These orange lights, on early evenings, hit the buildings and made them glow red. It was as if the city contained a mischievous red demon. This fiery color was no doubt the result of Yerevan's prettiest architecture: government buildings had been made from huge stone blocks whose clayey colors ranged from light orange to black orange.

I walked through this city, on the day I left Laura from New York's apartment - my final residence in Yerevan. I'd spent a week there. I liked warm-hearted and energetic Laura, and the Iranian brothers she lived with: young fluffy-haired Esfandyar, who believed in anarchy as did I; and Khashayar, who wore little hair except for a bushy Iranian moustache, and who believed aliens controled our governments and that's why they were so bad.

With renewed energy, I walked to Yerevan's "Genocide Memorial". I hoped to learn something about what all the Armenians were talking about.

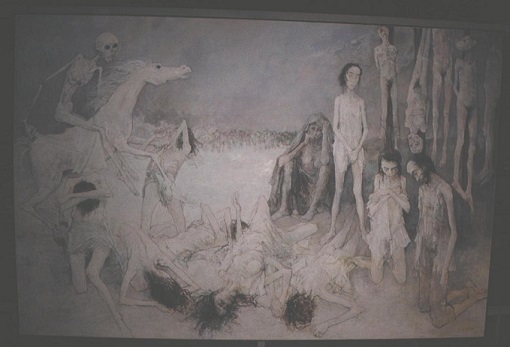

Laura had said this museum was worth visiting, just to see the biased way the information was presented. One of the first images I saw upon entering the museum was a cartoon drawing of Turks, wearing silk baggy clothes and beards and towels on their heads, using curved swords to kill defenseless Armenians. I wasn't sure if the museum considered items like these to be ridiculous propaganda, or if Armenians actually believed Turks were like that? Nevertheless, the fact that this stereotypical and unrealistic portrayal of Turks even appeared here was enough to somewhat discredit the museum's seriousness.

Away from the cartoonish propaganda and sensational novels villainizing Turks, the museum showed facts.

Documents, photographs, and statistics were shown. There was an appeal from President Woodrow Wilson to the American people to donate money to save Armenian orphans and refugees. Photos showed women starving, and kids who'd been exiled to the desert. Statistics showed population numbers of Armenian towns in Eastern Turkey, before 1915 and afterwards - when they were almost empty. These facts seemed to prove the genocide had taken place. But, I felt the museum's exhibits lacked psychological depth.

I wondered:

What had been Turkey's motive for doing this? Were they worried about having Armenian Christians in their land during World War I? (Armenians thought of Eastern Turkey as "Western Armenia".) And ... where were the first-hand accounts of the victims? Were there any stories of Armenian heroism?

Nearing the end of the museum's exhibits, I came upon an interesting first-hand account of the genocide. It came from a Danish missionary, Maria Jacobson, who'd lived in Turkey from 1907 to 1919. She'd written in her diary ...

On June 26, 1915, it was announced that all Armenians would be sent into exile.

On July 6th, boys over the age of nine were led from the town of Itchme to be killed. The soldiers and Kurds who killed them came back and visibly washed the blood off their clothes in the river.

On July 8th, it was announced that the remaining Armenian women and young girls should marry Muslims. Jacobson wrote: "The Kurds already take whatever girls they want."

She wrote, ten days later, that Turks took the Armenians' possessions when they were told to leave, before they'd even left.

On July 24th, it was announced that any Turk found hiding an Armenian would be hung and his house burned. All houses would be searched.

And on November 5th, Jacobson wrote that soldiers had dragged an elderly Armenian woman down a long set of stairs, while she was exhausted. Ten local boys followed, laughing at her.

I left Jacobson's first-hand account. I soon came upon a story of Armenian heroism.

In the summer of 1915, in a part of the Ottoman Empire that was presently Syria, five thousand Armenians fled from their hometown and took refuge on a mountain. Their number included six hundred able fighters. It was July 30th.

On August 7th, 10th, 19th, and September 9th, the Turks attacked them, with as many as fifteen thousand men. Each time, the Armenians defended their ground. They defended their mountain long enough for a French war-ship to come near land. Between September 10th and 15th, the ship rescued four thousand of the Armenians and brought them to Egypt.

This victorious struggle would be retold in a novel, "Forty Days of Mt. Mousa", by Franz Werfel. Turkey's government opposed the novel, which was published in 1935.

I walked on through the museum. I came to an exhibit discussing "cultural genocide": the destruction of a culture. The United Nations didn't recognize this phenomenon as a problem in its world. But, a European Council, in 1987, ordered that Turkey must respect the language, culture, and educational system of its remaining Armenians.

I next came to a New York Times article, dated July 13, 1919. It announced that a global court had condemned the three Turks who'd orchestrated the genocide - Enver Pasha, Talaat Bey, and Djemal Pasha - to death penalties. The three had already fled Turkey, though, and their whereabouts were unknown.

The article reported that two other men, one a Kurd, were sentenced to fifteen years of hard labor. And two others had been acquitted. One man, Kemal Bey, had already been executed. It seemed like a small number of people to be blamed for a genocide.

The article said that Enver, Turkey's Minister of War during WWI, was good friends with Germany. He'd fled to Germany before Turkey's surrender. He confidently predicted his country would be rescued by Germany once Bulgaria joined the Central Empires.

He and his two co-leaders once said the genocide had been necessary because Armenians were "troublesome". The two men whom the global court acquitted were considered to be nothing more than "tools" of the leaders. In addition, Kurds had been instigated to do most of the killing.

It was due to this fact that Laura from New York wondered: Why did Armenians consider Turkey to be their enemy, yet they were rather fond of Kurds? Had they forgotten that Kurds considered "Western Armenia" Kurdistan?

I finished my tour around the museum. But, I still had questions. I addressed them to a guide named Lousine, an Armenian in her twenties who specialized in genocide studies.

"Why had the Turks done it?"

She said they'd done it for "nationalism". They'd had the idea since 1908, and used World War I as an opportunity to implement it. They wanted the land to be for Turks.

I was a little unsatisfied with this answer.

I asked next, "Were Enver Pasha and his co-leaders ever found?"

Yes. The three were found and killed by the Armenian Revenge Takers - one of them in Germany, and Enver Pasha in Middle Asia.

Was Ataturk involved in the genocide?

No. He came to power in Turkey later.

I stepped out of the museum. It had been interesting. But, I wished the museum's exhibits could've been better arranged, to tell a fluid story of the progression of the genocide. I wished they spoke more deeply about the psychology of the participants, and concentrated on the people rather than the facts.

I was ready to leave Yerevan. But, one of the things I was going to miss most about the city was its views of Mt. Ararat.

After an especially cold night in the region, I'd woken up and looked at the mountain. Snow covered its broad bulging summit, and beneath this bulge were the much broader foothills which were the dull color of earth except for a thin cap of snow on the top. The bright snow floated in the sky. I tried to think, what did the shape of the snowy parts remind me of?

I found my answer! They reminded me of a boat. An ark.

Maybe Noah really had landed there!

Probably not. But, the Moses Oddyseus came close enough, in 2013, to reveal his final five commandments. They were, of course, the laws of the "Romantic Revolution":

"Thou shalt know the truth - that thy soul will live the lives of all other people - and thou shalt care about others knowing they are thou."

"Thou shalt be celibate."

"Thou shalt practice free love."

"Thou shalt accept all members of the opposite sex with kisses."

"Thou shalt include and welcome all people in thy family."

I looked at Mt. Ararat one last time.

And then, I began heading for Turkey. I was sure they would have something to say about the genocide.

peace,

Moses Oddyseus